What a High-Risk HPV Diagnosis Means (And How to Protect Yourself)

Quick Answer: Genital warts themselves do not cause cancer, but certain high-risk HPV strains that don’t cause warts can lead to cancer over time. Regular screening and knowing your HPV type are key.

“They Said It Was Just a Wart, But I Couldn’t Shake the Fear”

Melissa, 28, had just started seeing someone new when she noticed a tiny fleshy bump near her vaginal opening. Her primary care doctor identified it as a genital wart caused by low-risk HPV.

“She said it was harmless,” Melissa recalled, “but I didn’t believe her. How could an STD not be dangerous?”

Melissa’s response is understandable. In a culture where “HPV” and “cervical cancer” are often mentioned in the same breath, finding a genital wart can feel like a warning sign for something bigger. But here's the scientific breakdown: the types of HPV that cause visible warts, mainly types 6 and 11, are not the same types that cause cancer.

According to the CDC, over 90% of genital warts are caused by these low-risk strains. Meanwhile, high-risk types like HPV 16 and 18 often produce no visible symptoms at all, making them both more dangerous and more elusive.

People are also reading: Think You’re Immune to STDs? Not Without These Vaccines

HPV 101: Low-Risk vs High-Risk Types

There are over 100 known types of human papillomavirus, and about 40 of them infect the genital area. These are typically categorized as either low-risk or high-risk based on their cancer-causing potential.

Table 1: HPV type categories and their typical health outcomes. Low-risk types cause skin-level symptoms. High-risk types affect deeper cellular changes linked to cancer.

The tricky part is you can be infected with multiple HPV types at the same time. So someone with visible warts may also carry a high-risk strain, and not know it. That’s why testing and monitoring matter, even if the visible symptoms seem minor.

Why Genital Warts Look Scary, But Aren’t Cancerous

Genital warts tend to look dramatic: flesh-colored, bumpy, sometimes clustered like cauliflower. They often appear on moist skin, like the vulva, anus, penis, or scrotum. But despite their appearance, they’re rarely dangerous. In fact, they’re a sign your immune system is working: your body is reacting to the virus on the surface.

Unlike cancer, which involves the transformation of cells and tissues deep within the body, genital warts are external. They don’t burrow or mutate, they simply grow where the virus has activated. And in many cases, they go away on their own within 6–12 months, especially in younger people with strong immune responses.

Still, their presence can be emotionally painful. Many people describe shame, isolation, or even disgust. That emotional toll is real, and deserves care just as much as the physical symptoms.

Can Genital Warts Ever Turn Into Cancer?

The short answer is: not directly. Genital warts themselves are caused by HPV types that don’t trigger cancerous changes. However, having HPV at all, especially multiple strains, can increase your risk if one of those strains is high-risk.

Studies published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine show that while low-risk HPV types stay at the skin surface, high-risk types can integrate into the host’s DNA. That’s what begins the process of abnormal cell growth, which can eventually become cancer if not detected early.

This is why screening matters. If you’ve had genital warts, you should still get regular Pap smears (for cervix-bearing individuals), consider HPV genotyping, and talk with a provider about your risk profile.

Invisible Doesn’t Mean Harmless: Why High-Risk HPV Is Harder to Spot

One of the cruel ironies of high-risk HPV is that it’s usually silent. Unlike low-risk types that produce visible warts, the most dangerous strains typically show no symptoms. That means many people carry these cancer-linked types without ever knowing it, unless they’re regularly screened.

“I never had a single wart or bump,” said Andrés, 35, who discovered he carried HPV type 16 during a routine anal cancer screening offered through an LGBTQ+ community clinic. “If I hadn’t done that screening, I wouldn’t have known until it was maybe too late.”

HPV type 16 is the most notorious for its connection to multiple cancers, including cervical cancer, throat cancer, and anal cancer. Type 18 follows closely behind. These strains don’t produce warts, but they can alter the DNA in the infected area, leading to precancerous lesions.

This makes testing critical. Even if you feel fine, or have only seen a single wart, knowing whether you carry a high-risk strain can change your medical game plan dramatically.

What About Men? HPV, Warts, and Cancer Risk Outside the Cervix

Too often, HPV is framed as a “women’s issue,” largely due to its link with cervical cancer. But this narrative leaves men, and people without a cervix, at risk of misunderstanding their vulnerability.

In reality, HPV can cause cancer in all genders. Anal, penile, and oropharyngeal (mouth/throat) cancers are increasingly linked to high-risk HPV strains, especially among men who have sex with men (MSM) and unvaccinated individuals.

Here’s the issue: there’s no approved HPV screening test for the penis, anus, or throat in the general population. That means people assigned male at birth often go undiagnosed unless they present with visible warts or undergo specialized anal Pap tests in high-risk groups.

“We need to shift the conversation,” says Dr. Marcus Hall, a sexual health researcher in Chicago. “HPV is not gendered. It’s a viral infection that can affect everyone, and so prevention and education must include everyone too.”

This is especially important because men are less likely to seek out care for genital warts due to stigma, confusion, or the mistaken belief that it's "just cosmetic." And that can lead to both missed diagnoses and ongoing transmission.

Can You Have HPV Without Warts? Yes, And That’s Where It Gets Risky

One of the most confusing aspects of HPV is that most people with it have no idea. According to the World Health Organization, around 80% of sexually active individuals will contract at least one type of HPV in their lifetime. The vast majority never develop symptoms.

That’s because the immune system often clears the virus naturally within one to two years. But in some people, high-risk HPV persists, silently changing cells. This is why regular Pap tests and HPV screening are critical for anyone with a cervix. It’s also why genital warts, though frightening, can actually act as a wake-up call for broader HPV awareness and testing.

If you're worried about your risk but have no symptoms, you can still test. Some STD test kits now include HPV-specific panels for high-risk strains, or you can talk with a provider about in-clinic options like colposcopy or anal Pap screening depending on your anatomy and exposure history.

People are also reading: STD or Skin Irritation? What Red Spots on Your Vagina Really Mean

How Long Can HPV Stay Dormant in the Body?

This is one of the top search queries from people spiraling after a wart diagnosis: “Could I have gotten this years ago?” The answer is: yes. HPV can lie dormant for months, or even years, before symptoms appear or become detectable through testing.

Researchers estimate that HPV latency can last anywhere from 6 months to over a decade in some individuals. This makes it nearly impossible to pinpoint when you contracted it, or from whom. The virus may have entered your system from a partner years ago, only to reactivate when your immune system was weakened due to stress, illness, or other infections.

This also means that testing “after exposure” can be tricky. You might test negative shortly after sex, only to have the virus emerge later. That’s why retesting, regular screening, and follow-up exams are so important, especially if you’ve had multiple partners, are immunocompromised, or are dealing with persistent symptoms.

“I Got the Vaccine, Am I Still at Risk?”

Jared, 25, got the HPV vaccine as a teen. “I thought I was good,” he said. “But then I noticed a wart and completely freaked out.” His story reflects a common point of confusion: the vaccine protects against certain high-risk and wart-causing types of HPV, but not all of them.

The CDC recommends the HPV vaccine for everyone through age 26, and for some up to age 45 depending on risk factors. The most common vaccine, Gardasil 9, protects against HPV types 6, 11 (wart-causing), and 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 (high-risk cancer-causing types).

That’s great protection, but not full immunity. You can still contract or carry non-covered strains. And if you were exposed to HPV before vaccination, the shot won’t reverse infection, it can only prevent future ones. That’s why vaccinated individuals should still test regularly and monitor for symptoms or changes.

Bottom line? The vaccine is powerful, but not a guarantee. Think of it like a seatbelt: it dramatically reduces harm but doesn’t mean you should drive without looking at the road.

Testing, Typing, and What to Do If You’re Not Sure

Here’s where things often get overwhelming: you’ve seen a bump, or you’ve had a partner disclose HPV, and now you’re stuck wondering, “What type do I have?” or “Do I need to worry about cancer?” The answer depends on what kind of testing you get, and what part of your body is involved.

For individuals with a cervix, routine Pap smears and HPV co-testing (where the sample is also typed for high-risk strains) can catch abnormal changes early. If anything suspicious is found, a colposcopy may be recommended to take a closer look at cervical tissue.

For others, including men and nonbinary individuals, options are less standardized. However, you can:

- Use at-home kits to screen for high-risk HPV strains (some now include vaginal swabs or urine-based tests).

- Request anal Pap smears if you’re in a higher-risk group, such as MSM, people living with HIV, or anyone with a history of receptive anal sex.

- See a dermatologist or sexual health provider for wart identification, biopsy (if needed), and guidance on risk level.

Remember: testing isn’t just about knowing if you have HPV. It’s about knowing what kind, and what to do next.

When to Test, What to Test For

Table 2. Different testing options depending on symptoms and anatomy. Always confirm test accuracy and method with a licensed provider.

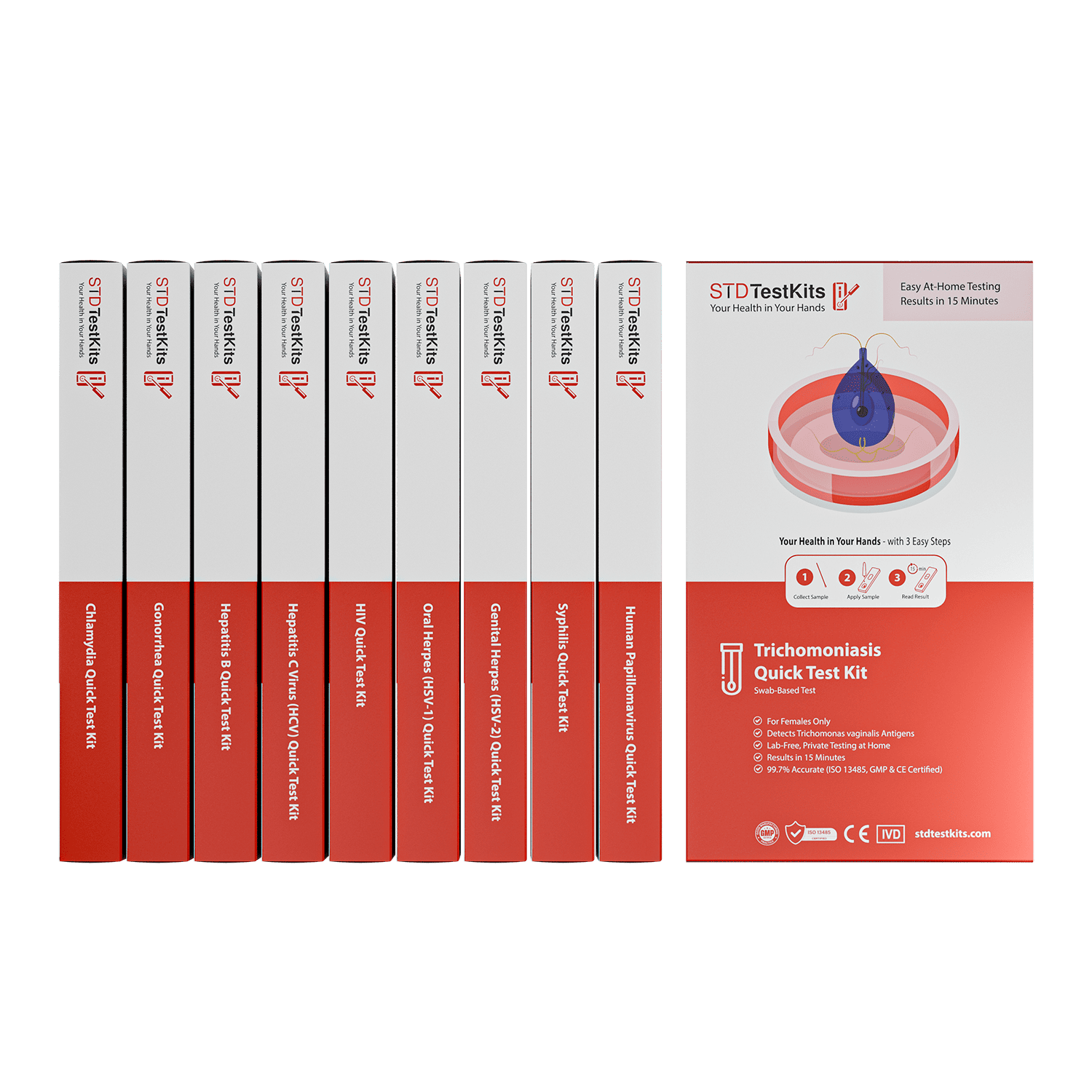

Don't Wait and Wonder, Get Tested from Home

If you’re worried about HPV but feel too anxious or embarrassed to go to a clinic, you’re not alone. Many people delay care out of shame, uncertainty, or fear of judgment. That’s why at-home testing has become such a critical tool in sexual health access.

With an FDA-approved Combo STD Home Test Kit, you can screen for multiple infections in the privacy of your home. Some kits now offer high-risk HPV testing for cervix-bearing individuals, and include easy instructions for sample collection and mailing.

These tests aren’t just convenient. They’re empowering. Taking the step to test, even when it’s scary, gives you back control. Whether you’re dealing with symptoms, a recent hookup, or just a persistent “what if,” you deserve clarity.

Why Shame Doesn’t Belong in a Medical Diagnosis

Let’s be real, there’s a lot of silence, judgment, and misinformation around genital warts and HPV. Many people feel gross, guilty, or damaged after a diagnosis. But here’s the truth: this is a virus. A common one. One that nearly everyone will encounter in their life if they’re sexually active.

HPV is not a moral failing. You didn’t “ask for it.” You didn’t fail by not knowing. This isn’t about purity, it’s about biology, exposure, and how viruses work. No one deserves to feel dirty because of a skin change.

And while it's true that high-risk HPV can be serious, it’s also true that early detection, vaccination, and regular care can stop cancer before it starts. That’s the power of education, and the opposite of fear.

You’re not alone. You’re not gross. You’re not doomed. You’re human, and you have options.

FAQs

1. So… do genital warts mean I have cancer?

No, and take a breath. Genital warts are annoying, stressful, and emotionally heavy, but they’re not cancer. They’re usually caused by low-risk HPV types (6 and 11), which don’t have the ability to mutate your cells the way high-risk types like 16 or 18 can. But, and this is important, it’s possible to have both low- and high-risk HPV at the same time, which is why testing and follow-up matter.

2. Can you have HPV and never know it?

Absolutely. In fact, that’s the norm. Most people who carry HPV never get a single symptom, not a bump, not a wart, not even a weird tingle. It lives quietly in your system, sometimes for years. That’s why it spreads so easily, and why screenings like Pap tests and HPV co-testing are so crucial for catching what you can’t see.

3. If I don’t have warts, can I still have a cancer-causing HPV type?

Yes, and here’s where HPV is a bit of a trickster. The types that cause cancer are usually the ones that don’t leave any visible signs. That’s what makes them dangerous. Just because your skin looks fine doesn’t mean there’s nothing happening deeper down. It’s not about panic, it’s about staying informed and checking in with your body.

4. Can guys get cancer from HPV too?

Yes, and it’s not talked about enough. HPV can lead to anal, penile, and throat cancers in people assigned male at birth, especially those who have sex with men or are immunocompromised. But because there’s no routine screening for HPV in men, these cancers often go unnoticed until they’re more serious. We need better awareness, not just for women but for everyone.

5. I got the HPV vaccine. Why did I still get a wart?

The vaccine is amazing, but it’s not a force field. Gardasil 9 protects against 9 types of HPV, including the ones most likely to cause cancer and genital warts. But there are over 100 HPV types. If you got exposed to a type not covered, or were exposed before you got vaccinated, you can still develop symptoms. It doesn’t mean the vaccine failed; it means HPV is a big viral family.

6. Can I get HPV again after it goes away?

Unfortunately, yes. Clearing the virus doesn’t mean you’re immune for life. It just means your body suppressed it this time. You can get re-infected with the same type, or a different one, especially if your partner carries it. That’s why barrier protection, vaccination, and retesting matter even after symptoms disappear.

7. Can you pass on HPV even if you don’t have symptoms?

Yep. That’s the kicker. You can feel 100% fine, look totally clear, and still pass it on during skin-to-skin contact. HPV doesn't need fluids to spread, it travels through direct genital contact, sometimes even with a condom. That’s not a reason to panic, it’s just a reason to stay tested and be upfront with partners.

8. Is there an at-home test for HPV?

For some people, yes. If you have a cervix, there are now at-home kits that let you self-swab and mail in the sample to check for high-risk HPV types. They’re not as comprehensive as in-clinic Pap smears, but they’re a solid start. If you don’t have a cervix, testing gets trickier, there’s no approved home test for HPV in men (yet), but you can still get other STD panels delivered discreetly.

9. If I test positive for high-risk HPV, what do I do?

First: don’t spiral. Testing positive means you’ve caught something early, and that’s a good thing. It doesn’t mean you have cancer. It means you need monitoring. Your provider may suggest repeat testing, colposcopy, or follow-up Pap exams. Most HPV infections, even high-risk ones, clear up on their own. Your job is to keep an eye on things, not blame yourself.

10. Do genital warts ever go away on their own?

Often, yes. A lot of people see warts vanish within 6–12 months as their immune system fights off the virus. But they can come back, sometimes years later. Treatment options include freezing, topical meds, or surgical removal, but they don’t “cure” the HPV itself. Think of wart treatment like mowing the lawn: it handles what’s visible, but the roots might still be there.

You Deserve Answers, Not Assumptions

HPV can feel overwhelming, especially when it shows up uninvited and unclear. But now you know the difference between hype and real risk. You know that genital warts don’t mean cancer. You know what types matter, when to test, and how to protect yourself.

What you do next isn’t about shame or panic. It’s about clarity. If you’re worried about HPV or just want peace of mind, you can order an at-home STD test kit here, quick, discreet, and medically trusted.

Don’t let the unknown keep you up at night. You deserve answers. And you deserve them without judgment.

How We Sourced This Article: We combined current guidance from leading medical organizations with peer-reviewed research and lived-experience reporting to make this guide practical, compassionate, and accurate. In total, around fifteen references informed the writing; below, we’ve highlighted some of the most relevant and reader-friendly sources.

Sources

1. WHO – HPV and Cervical Cancer Fact Sheet

2. American Cancer Society – What Is Cervical Cancer?

3. Planned Parenthood – HPV Overview

4. National Cancer Institute – HPV and Cancer

5. Mayo Clinic – Genital Warts: Symptoms and Causes

About the Author

Dr. F. David, MD is a board-certified infectious disease specialist focused on STI prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. He blends clinical precision with a no-nonsense, sex-positive approach and is committed to expanding access for readers in both urban and off-grid settings.

Reviewed by: N. Greene, NP-C | Last medically reviewed: January 2026

This article is for informational purposes and does not replace medical advice.