Polyamory and STDs: Are You Really at Higher Risk?

Quick Answer: STDs have existed for thousands of years, but how we’ve responded, from ancient blame games to modern breakthroughs, has been shaped more by stigma, war, and cultural panic than science. Today’s testing tools evolved from centuries of trial, error, and survival.

Before We Had a Name for It: STDs in Ancient Civilizations

Let's go back a long time, before antibiotics, germ theory, and microscopes. The Ebers Papyrus, an ancient Egyptian scroll from around 1550 BCE, talks about genital ulcers and discharges that sound a lot like modern gonorrhea and chlamydia. Ayurvedic texts from ancient India describe conditions that sound a lot like syphilis: painful sores, fevers, and swollen lymph nodes. In China, doctors wrote down symptoms that we now know are sexually transmitted and treated them with herbal infusions and moxibustion, which is a type of heat therapy.

But here's the thing: these cultures didn't just see STDs as health problems. They thought of them as moral failures, curses, or spiritual imbalances. Sexually transmitted infections were linked to taboo, ritual, and punishment. If you were sick "down there," you were dirty, both physically and spiritually. This way of thinking didn't just stay the same; it got worse over time.

By the time the Roman Empire hit its peak, public baths were booming, and so were STDs. Writers like Galen and Pliny the Elder referenced genital sores and pain during urination, sometimes attributed to “excess of pleasure.” Yet instead of effective treatment, people turned to wine, vinegar, or “purging” rituals. The problem? No one knew what caused these illnesses. And without knowledge, people blamed what they feared: sex itself, or the people having it.

People are also reading: When to Test for Syphilis After Exposure (And When Not To)

Syphilis Takes Center Stage, And the Blame Game Begins

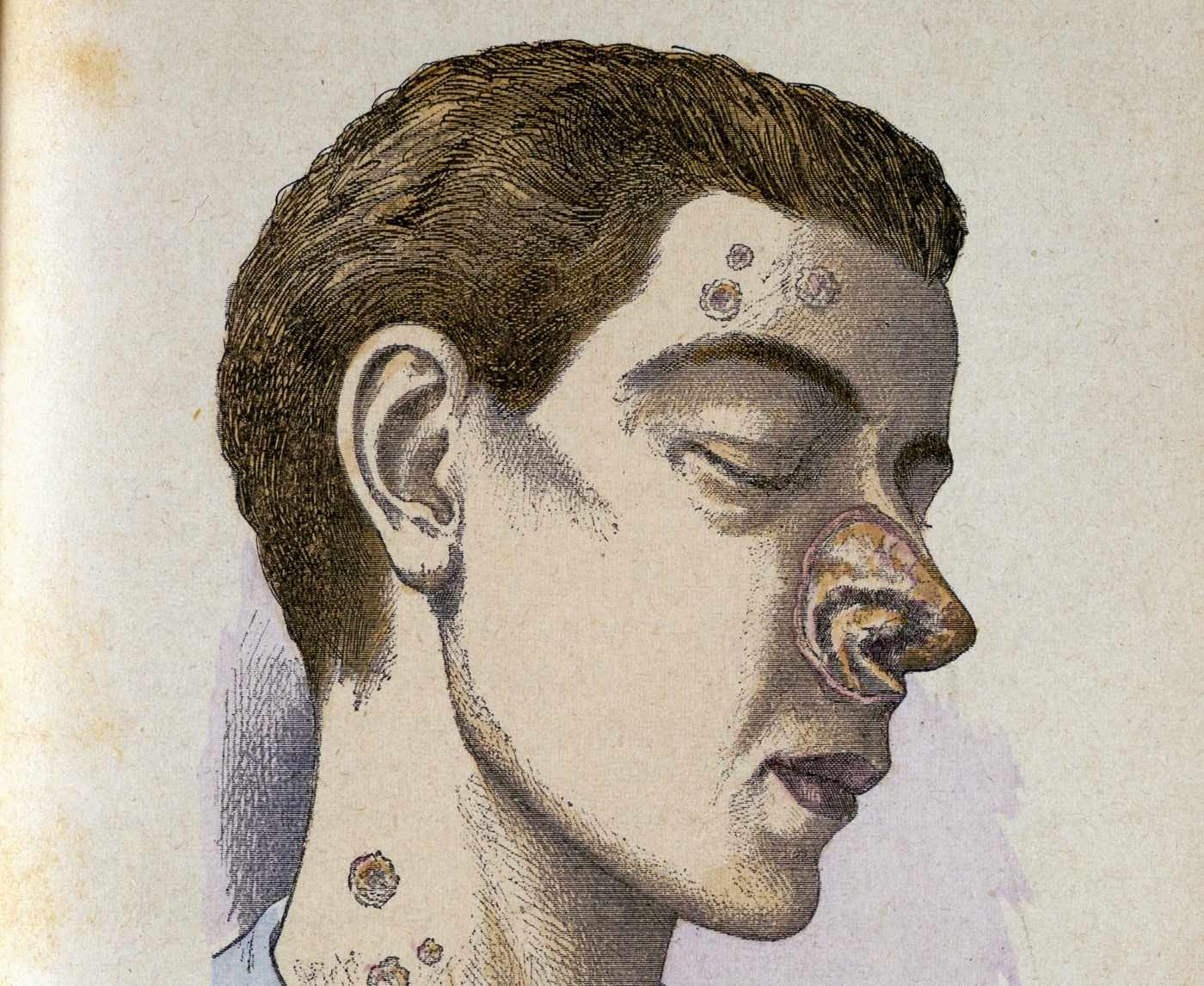

In 1494, the French army laid siege to Naples. What followed was a deadly outbreak that spread rapidly through Europe. Soldiers developed horrifying symptoms: skin ulcers, bone pain, and facial disfigurement. What we now know was an early strain of syphilis was so aggressive it earned dramatic nicknames depending on who you asked: the “French Disease” in Italy, the “Italian Disease” in France, and the “Christian Disease” in the Ottoman Empire. Nobody wanted to own it, so they blamed the next country over.

Early syphilis was brutal. Some accounts describe victims “melting” from the inside out. There was no cure, and many treatments made things worse. The most popular? Mercury. Applied topically, swallowed, or even injected, it caused teeth to fall out, muscles to seize, and minds to fracture. Physicians knew mercury was dangerous, but in their eyes, death by poison was better than death by syphilis. That says everything about the desperation of the time.

Here’s a sobering glimpse into the logic of 16th-century medicine: if you started salivating uncontrollably, doctors saw it as a good sign, proof the mercury was “working.” In reality, your body was being slowly destroyed from the inside.

Table 1. Early STD treatments before modern medicine. Often more harmful than helpful, these remedies reflect how desperation, stigma, and misinformation shaped patient care.

The name “venereal disease,” derived from Venus, the Roman goddess of love, became popular in the Renaissance era. A dark irony, considering how many people suffering from these illnesses were anything but romanticized.

Sex, Shame, and Snake Oil: The Rise of “Cures” That Killed

Fast forward to the 1800s. Sex work, urbanization, and the rise of “moral medicine” collided, and STDs exploded in cities like London, Paris, and New York. But so did snake oil salesmen. In the absence of regulated medicine, people turned to apothecaries and quack doctors promising secret cures, miracle potions, and “discreet packages.” If this sounds familiar, it should, today’s sketchy online pharmacy ads are just the modern version.

Advertisements from this era pushed cures for “private diseases” with heavy euphemisms. These weren’t medical pamphlets, they were shame-filled, fear-fueled sales pitches. Products like Clarke’s Blood Mixture or “Professor Holloway’s Pills” claimed to cleanse the blood and restore manhood. Most were alcohol, opiates, or heavy metals, offering momentary relief followed by long-term harm.

Here’s where the tragedy deepens: people couldn’t talk about their symptoms publicly. Going to a real doctor meant risking exposure, scandal, or even arrest. In some cases, women were institutionalized for having syphilis, especially if they were sex workers or poor. For queer people and immigrants, an STD diagnosis could lead to deportation or criminal charges. The shame was baked into the system.

Lena, 19, fictionalized from real accounts, lived in New York in 1897. After developing a rash and internal pain, she visited a chemist under a fake name. He sold her a “restorative tonic.” The pain worsened. By the time she saw a hospital doctor weeks later, her syphilis had spread to her brain. She died of neurosyphilis six months later. Her family never knew the real cause.

Wartime Sex, Military Panic, and STD Surveillance

Wars have a way of revealing what a society actually cares about, and by World War I, governments cared deeply about keeping soldiers “clean.” But not clean as in bathed, clean as in disease-free. For militaries, STDs weren’t just a health issue; they were a threat to manpower, discipline, and public image. In 1917 alone, the U.S. Army reported over 100,000 cases of gonorrhea and syphilis, making them two of the top reasons soldiers were taken off duty.

Instead of asking why infection rates were so high, military leadership focused on controlling sexuality. Brothels near army bases were shut down. Propaganda posters warned troops about “loose women” and “venereal traps.” If a soldier got infected, he could be court-martialed, not for getting sick, but for putting the war effort at risk.

One pamphlet distributed in WWI read: “A minute with Venus, a lifetime with Mercury.” The implication was clear: sex was dangerous, and catching an STD meant you’d be punished, with shame, poison, or both.

By WWII, medicine had improved, but so had surveillance. Soldiers were often required to undergo regular genital inspections. Clinics were set up on-site to deliver rapid mercury injections or early versions of sulfa drugs. The turning point came in 1943, when penicillin entered the picture. For the first time in history, syphilis had a real, effective cure that didn’t destroy the patient in the process.

Table 2. Wartime STD policies reflect how public health often collided with control and propaganda, long before privacy or consent became medical priorities.

Still, access was everything. While U.S. troops were getting penicillin, civilians, especially Black Americans, queer folks, and sex workers, were often denied access or used in unethical trials. The most infamous? The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where Black men were denied treatment for 40 years so researchers could observe the “natural progression” of the disease. It was one of the darkest chapters in American medical history, and the damage to public trust persists even today.

Modern Testing, Old Shame: The HIV Crisis Changes Everything

The 1980s arrived with neon lights, disco hangovers, and a mysterious illness doctors first dubbed “GRID”, gay-related immune deficiency. We know it now as HIV, and the virus shook the medical world to its core. But more than that, it shattered the illusion that STDs were either curable or someone else’s problem.

At first, testing was experimental and limited. Getting a diagnosis meant being marked, by insurance companies, employers, or the law. In some states, even getting tested for HIV required signing your name to a government database. The result? Thousands of people chose not to test at all.

Ramon, 33, fictionalized from multiple survivor accounts, lost three partners to HIV in the early ‘90s. He didn’t get tested himself until years later.

“I was scared,” he recalls. “Not of dying, but of what they’d do to me if I tested positive. Would I lose my job? My apartment? My dignity?”

Fear of the test, not just the disease, defined a generation.

It wasn’t until 1996, with the arrival of antiretroviral therapy (ART), that HIV began to shift from a death sentence to a chronic condition. But the trauma didn’t evaporate. To this day, HIV stigma still shapes how people approach STD testing as a whole, especially in queer communities and communities of color.

How STD Testing Finally Went Private, But Not Always Equal

The modern at-home test kits many of us now rely on didn’t appear overnight. They’re the result of decades of slow, sometimes painful, progress. In the late 2000s, early mail-in services were launched for people too scared, or too busy, to go to a clinic. But at-home tests weren’t cheap, and early versions lacked accuracy. Still, they opened the door to what many had been waiting for: privacy, speed, and autonomy.

Today, FDA-cleared kits like those from STD Test Kits offer reliable results in under 20 minutes from the comfort of your bathroom. For people living off-grid, in rural areas, or with limited transportation, that’s not just a convenience, it’s a lifeline.

But testing access is still uneven. In many places, STI clinics are underfunded or shut down completely. Teens may need parental consent. Immigrants might avoid testing out of fear. People with disabilities often face logistical nightmares just to get screened. So while the tech has advanced, the systems haven’t always caught up.

One major lesson from history? A test is only as powerful as a person’s ability to access and trust it. And trust, once broken, takes more than penicillin to repair.

People are also reading: How Long After Exposure Can Chlamydia Be Detected?

Names Matter: From “Pox” to “Shameful Secret”

The way we name diseases says a lot about what we fear, and who we’re willing to blame. In the past, STDs were rarely named after pathogens. They were named after people, places, or moral judgments. “The French Disease,” “the Neapolitan Disease,” “the Spanish sickness,” “the Great Pox.” By slapping a foreign label on a sexually transmitted disease, countries could deflect shame onto someone else’s bedroom.

Even in the 20th century, euphemisms reigned. People said they had “VD” (venereal disease) or “a social disease.” Clinics were called “hygiene centers,” and pamphlets avoided any language that sounded like sex. One famous line from a U.S. Army training film: “You may think she’s clean. You may be wrong.”

Modern medicine brought a new language, clinical, precise, often cold. Gonorrhea. Chlamydia. Trichomoniasis. But culturally, the shame stuck. The renaming didn’t erase the fear or judgment. It just made it harder to talk about. When words change but the silence remains, stigma survives.

The Bizarre, Sometimes Deadly World of STD “Cures”

Long before antibiotics, the world tried just about everything to treat sexually transmitted infections, many of them dangerous, some of them downright ridiculous. In the Middle Ages, it wasn’t uncommon to prescribe leeches to the genitals, believing they would “suck out the disease.” In Victorian England, electric belts and copper “anti-venereal” devices were sold in medical catalogs, worn under clothing to supposedly ward off syphilis or “regulate lust.”

Gold injections, tobacco smoke enemas, arsenic pills, steam baths, goat urine compresses, you name it, someone tried it. And like today’s snake-oil supplements pushed on social media, these cures often promised what real medicine couldn’t: discretion, restoration, purity.

Elijah, 40, a modern-day herbalist who grew up in rural Mississippi, recalls his grandmother sharing “remedies” for STDs: boiled pine bark, honey-soaked garlic, and fasting for three days.

“It wasn’t about what worked,” he explains. “It was about doing something. Anything. Because going to a clinic meant gossip. Shame. Exposure.”

Table 3. Historic STD “cures” reveal how desperation, social pressure, and lack of scientific understanding drove treatment trends, often with dangerous consequences.

STDs in Pop Culture: Punchlines, Plot Twists, and Silence

By the time we reached the television age, STDs had become either punchlines or horror stories, rarely anything in between. Sitcoms used herpes as shorthand for promiscuity. Talk shows turned HIV into tabloid fodder. Films portrayed syphilis as punishment or tragic irony, especially in stories involving sex workers or queer characters. It wasn’t just lazy writing, it was inherited stigma, repackaged for prime time.

Even celebrities weren’t safe. Rumors about musicians, politicians, and Hollywood stars having herpes or syphilis circulated like wildfire, often with no proof. The idea wasn’t to inform, it was to humiliate. Publicly associating someone with an STD remained a way to shame them into silence or obedience.

And yet, every time a major figure spoke up, Magic Johnson with HIV, Pamela Anderson with hepatitis C, it cracked the shame just a little. Representation matters. Even in stories about disease. Especially in those.

Today, we’re finally seeing more honest conversations: TikToks about getting tested, YouTubers sharing their diagnosis stories, TV shows depicting STDs as medical conditions, not moral judgments. But for every voice speaking truth, there are still millions searching quietly, too scared to even ask. That’s why this history matters.

FAQs

1. Are STDs really that old?

Oh, they're ancient. Like hieroglyphs-and-sandals ancient. Long before anyone called them STDs, people were dealing with strange sores, odd discharges, and painful urination. Egyptian scrolls and Indian medical texts describe things that sound a lot like gonorrhea and syphilis. They didn’t have the science, but they had the symptoms, and the shame.

2. Why did they call syphilis the “French Disease”?

Because humans love blaming each other. Italians blamed the French. The French blamed the Neapolitans. The British blamed... everyone. Naming it after another country was a way to say, “This isn’t our fault. It’s theirs.” It's the epidemiological version of passing the hot potato.

3. What’s the weirdest thing people tried to cure STDs?

Mercury is high on the list. People rubbed it on their skin, drank it, even inhaled it, all in the name of fighting syphilis. Others went for tobacco smoke enemas (yes, really) or boiling herbs into genital steams. One 18th-century ad promised to cure “intimate afflictions” with crushed beetles and wine. People were desperate, and desperate makes weird decisions.

4. When did we finally get real treatments?

Penicillin was the game-changer. By the 1940s, syphilis went from deadly to curable, if you could access care. Before that, treatments were a toxic gamble. Salvarsan, an arsenic-based injectable, helped some but harmed plenty. Penicillin was the first true win.

5. Was STD testing always this private?

Not even close. In past decades, testing could mean registering with the government, being labeled “unclean,” or worse. During the HIV panic in the '80s, some people avoided testing out of fear they’d lose their jobs or health insurance if they tested positive. Privacy wasn’t a given, it was a privilege.

6. Did people even know how these infections spread?

For centuries, not really. They blamed bad air, bad morals, or even bad luck. Germ theory didn’t click until the 1800s. Until then, people thought “impure thoughts” or “unholy acts” brought on disease. The science was fuzzy, but the judgment? Crystal clear.

7. How did the HIV crisis shift everything?

It forced the world to face the human cost of silence. People were dying, and instead of care, they got cruelty. Testing became a political weapon. Stigma hit hard, especially in queer communities. But activism rose, science caught up, and slowly, we built something better, testing, treatment, and conversations that didn’t start with shame.

8. Why do people still fall for sketchy STD cures?

Because fear makes slick promises hard to resist. Even now, folks see ads for “cleansing teas” or “natural detox kits” online and hope for an easy fix. But the only thing those products usually clean out is your wallet. If it sounds too magical to be real, it probably is.

9. Are home tests actually reliable?

Yes, but only if real businesses make them. Some at-home kits have been approved by the FDA and are very accurate, especially if you use them at the right time after being exposed. The key is to follow the directions and not get ahead of yourself. Privacy and accuracy? You can definitely have both.

10. Why is STD stigma still such a thing?

Because it was never just about health. STDs have been framed as punishment for sex, especially the kind society doesn’t like to talk about. That shame got baked into culture, religion, and even medicine. It takes time to undo that kind of messaging, but every honest conversation helps melt the ice.

From Curses to Clarity: Where We Go From Here

It's not just about old diseases or strange treatments; STD history is also about silence, survival, and the stories we've passed down. The path hasn't been straight, from syphilis that acts like a plague to shame that can be used as a weapon to new treatments that change everything. But progress is being made.

If there’s one takeaway, it’s this: the weird, wild history of STDs shaped everything we know, and fear, about testing today. But it doesn’t have to define your choices. You don’t need permission to take control of your health. You just need access, information, and a little courage.

Whether you’re looking for peace of mind or starting fresh, you can test for STDs privately, accurately, and affordably from home. No judgment. No clinics. Just answers.

How We Sourced This Article: We looked at peer-reviewed medical journals, historical records, public health records, and firsthand accounts to put together a timeline of sexually transmitted diseases over the years. This article was based on about fifteen trustworthy sources. Below, we've highlighted some of the most useful and easy-to-read ones.

Sources

1. History of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) — PubMed

2. History of Venereal Diseases from Antiquity to the Renaissance — PubMed

3. History of Sexually Transmitted Disease — News-Medical

4. CDC Museum: Venereal Disease Program

5. Britannica: Sexually Transmitted Disease

About the Author

Dr. F. David, MD is a board-certified infectious disease specialist focused on STI prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. He blends clinical precision with a no-nonsense, sex-positive approach and is committed to expanding access for readers in both urban and off-grid settings.

Reviewed by: Leah Muñoz, MPH | Last medically reviewed: October 2025

This article is for informational purposes and does not replace medical advice.